Integrating our Racialized Selves

Growing up as a biracial Black child, I experienced a lot of confusion about my identity, and racism in response to it. I was born in Portland, Oregon at Emmanuel hospital and immediately moved to Rock Springs, Wyoming to live with my maternal grandparents. My mother was young (18) and wanted to be close to her parents, having not been in a committed relationship with my dad she felt little interest in staying in Portland to raise her first child.

I lived in that small town in rural America for eight years. During that time, I was surrounded by mostly white folks. A google search of the Rock Springs population in 1990 (four years into my life) states that there were 19,134 people and according to the 1990 census 92.9% of those people were white. As you can imagine, I stood out. I was often the only Black person at the grocery store, at my elementary school, and playing at any park. My grandparents are white, my mother is white, and until someone told me— I was white.

This is just the beginning of my story. I spent most of my life feeling out of place and without community. It wasn’t until my Freshman year at Portland State University in a Black Studies course that I felt connected to being Black and part of a larger community. This isn’t to say that I didn’t feel responsible for other people who looked like me. I did, in the sense that I knew my mistakes would be held against people I didn’t know. I also experienced people calling me other Black women’s names, and I would often be reminded of Black people that my peers had met or knew. All of this WAS the case, but I didn’t feel connected to my Blackness in a positive way. It instead felt like a weight I carried. I felt that weight until my undergrad in college when I was introduced to the work of Dr. Janet Helms and Joy & John Hoffman. They changed my life, so much so that I have utilized their work in my life ever since.

Because race is a social construct, most of us are born unaware of our race. The social construction of race can be described as the way we, as individuals and groups, become aware of our race and the race of others. Because awareness of race varies within and across societies, there has been curiosity and research happening for generations.

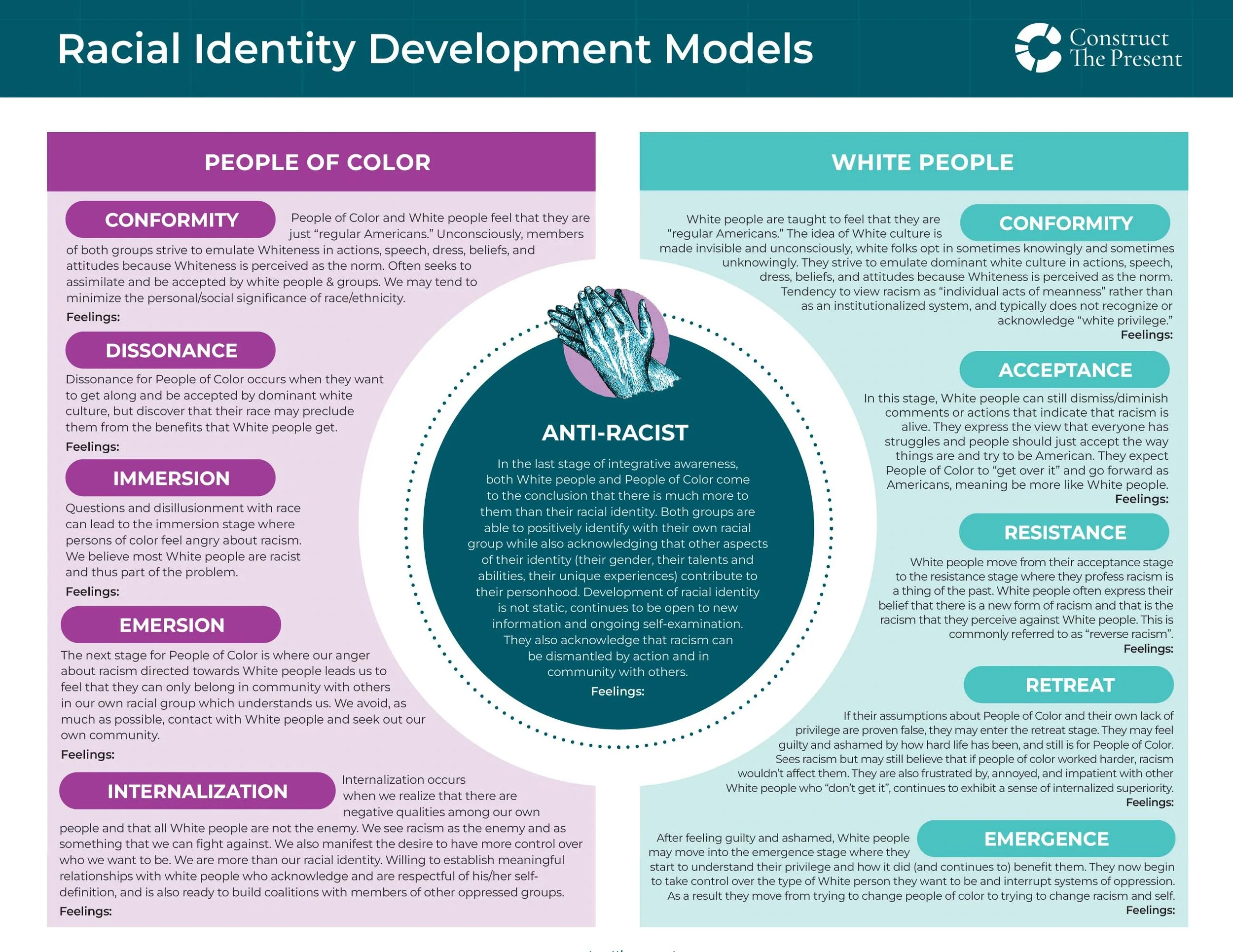

In the last few decades, the study of racial identity development has lived within psychology and education systems, with the goal to understand the range of experiences individuals encounter as they become aware of their race. The development models from this research shed light on how we function in relation to the identities we hold and also help us to build empathy for others who are in a different place than us. Ultimately, these models are designed to support everyone’s development towards a more integrated and anti-racist identity.

At Construct The Present our team of facilitators and strategists aim to co-create a future that is equitable and inclusive of all races, genders, and sexual orientations. We use the framework below to support our work with organizations and the individuals that lead them. Creating inclusion must include our own individual and collective healing. With that in mind, our work continues to be informed and inspired by Dr. Janet Helms (White Racial Identity Model) and Joy and John Hoffman (Integrated Model).

We believe that in order to move towards greater collective action in dismantling the oppressive systems of today, the work must begin with ourselves on an individual level. This model is a great place to begin this self-reflective journey.

Although racial identity models have traditionally been used by professionals in therapeutic and educational spaces as a means to more deeply understand patients and students, we encourage the application of this model more broadly in community and organizational settings.

Today, a range of models exist designed for different racial identities, all with similar visions of an integrated society.

Here are a few things to be aware of before beginning this reflection:

Everyone who embarks in racial identity reflections will have their own journey.

It’s feasible for you to revisit stages multiple times in a lifetime.

These frameworks are just the beginning. Your lived experience may take you to new places. There are infinite possibilities.

As part of your process, either individually or with your community, consider the below prompts to guide you in reflection:

What does race mean to you?

When did you first become aware of your race? The race of others?

Who taught you about race? At what age?

Do you feel connected to your racial identity? How come?

What have been major shifts in your understanding and awareness of race? Your own race?

While Construct the Present uses the integrated tool above for racial identity modeling, there are other resources available developed for African Americans, Asian Americans, American Indians, Latinos, as well as Bi-racial people and white people. Here is a helpful place to begin exploration if it serves your needs.

Racial Identity Development Models - © Construct the Present.

Sometimes theoretical research can be devoid of personal application. To support the application and use of this model, let’s look at the integrated model through my racial autobiography: I am biracial (Black and white) and identify as Black so I will be referencing the People of Color Model on the left-hand side. I’m going to share my racial autobiography so we can see how this model looks within a lived experience.

Stage 1: Conformity

The first stage of the integrated racial identity model is conformity. People of color feel that we are just “regular Americans.” Unconsciously, we strive to emulate whiteness in actions, speech, dress, beliefs, and attitudes because whiteness is perceived as positive.

Growing up in a predominantly white city and raised by a white mother I felt as though I was white until the age of 5. My mother tells the story of my 5th birthday (I remember it vaguely) when I asked for a Betsy Wetsy Doll. For those of you who don’t remember or didn’t have the pleasure of being exposed to this doll, it was a doll that I would take a bath with and then teach how to use the potty because otherwise, it would wet the bed, hence the name. For whatever reason, this is what I wanted for my 5th birthday. I asked for it over and over again and on October 9th, 1991 I received it. However, this morning 5-year-old Alexis was extremely disappointed.

I was disappointed because the doll I received had dark brown skin and an afro. In my mind, the doll I was asking for, was the doll on the television that had peachy skin and bouncy blond curls. At that moment I realized my family saw me as different than I saw myself and I moved into a state of dissonance with my racial identity. In all honesty, I believe my grandmother, the purchaser of this gift, meant well and wanted me to see myself reflected in the toys I played with. Unfortunately for me, neither my grandmother nor myself had awareness of institutional racism and the way it has a chokehold on marketing. As a result of that chokehold, that particular version of the doll was not in the commercial that I saw. That coupled with the fact that race and racism largely go unnoticed or talked about in white households I had not experienced myself as a Black young woman and confusion began for me as the outside world collided with my internal lived experience.

Stage 2: Dissonance

Dissonance for people of color occurs when we want to get along and be Americans but discover that our race may preclude us from the benefits that white people get. We start to feel confused about the beliefs we hold about America and ourselves as we begin to see that racism may be impacting us.

The experience with Betsy Wetsy began my transition into the Dissonance phase, which, coupled with my entry into 1st grade in Rock Springs, Wyoming, cemented my awareness of being different and exposed me to my first experiences of racism.

Living in Rock Springs, My three younger siblings and I were four of the seven Black children in the city. In 1st grade, I remember having a crush on another 1st grader named Bernard. Bernard and I were the only Black 1st graders and often sat together at tables and paired as buddies. After two years of being in the same class, being partnered, and spending quite a bit of time together I began to have a crush on Bernard and told him in 3rd grade. His response to me was, “I don’t like Black girls.” He then began “dating” our classmate Whitney who was white with brown hair.

It was about this time I began to notice other subtle differences between the way I was treated and the way my peers who looked like Whitney were treated. I would often raise my hand but was the last to be called. My teachers didn’t choose me to read aloud or play princess characters when we role-played story books. I was the last called to lineup or the last dismissed from lunch to recess. My peers also commented on my body and expressed that it was shaped differently. I began to feel othered and wondered if it was my race. This is all at the age of 8.

My wonderings intensified just as a major transition in my life happened.

It was at this time my family moved to Gresham, Oregon. My race was definitely on my mind at school but there were many other things happening in my life that took my focus and attention. Moving to Gresham cemented my transition into the Immersion phase.

Stage 3: Immersion

Questions and disillusionment with race and racism result in feelings of anger about racism. People of Color begin to feel that most white people are racists and thus part of the problem.

At the age of 9 and moving into 4th grade I did feel angry as referenced above in the model. But I couldn’t quite place where that anger was coming from. In all honesty, it was coming from many different directions. Wherever it was coming from, it became directed at my 4th-grade teacher. After three years in school, I experienced feelings of isolation, being ignored by my teacher, and othered by my peers. As a result, I withdrew from class in every way beginning in 4th grade.

I refused to raise my hand. When I had a choice I sat in the back of the class and intentionally said “I don’t know” in the hopes I could disappear. My 4th-grade teacher was persistent in her strategies to engage me and little Alexis took this as a threat and became more defensive and oppositional. It got to the point that my parents were asked to come in for a parent-teacher conference to talk about my behavior. This anger and resentment continued in school until I transitioned to high school, where I moved into the Emersion phase.

Stage 4: Emersion

The fourth stage for people of color is emersion where our anger about racism directed towards white people leads us to feel that we can only belong safely with others in our own racial group because only they can understand us. In turn, we avoid, as much as possible, contact with white people and seek out people of our own race.

I started my 9th-grade year in Gresham with the same peers I spent the last three years of middle school. My experience of otherization extended beyond the classroom and into my social circles during middle school. Most people I talk to describe their middle school experience as a terrible time; they experience bullying and exclusion. My experience was no different except that it was layered with racism.

During my three years in middle school, I was given the nickname “Missy Elliot.” Her song, The Rain, came out and because there were so few Black teenagers at my school people made the automatic connection, even though I look and looked nothing like Missy Elliot. No shade but watch the video and look at the referenced photos of myself. Nonetheless, I never was able to shake it. The comments about my body and hair continued and impacted me so much that I dyed my hair blond in 7th grade and began wearing baggier clothes to hide the curves of my body that did not exist with the rest of my peers.

After years of feeling alone and lonely and another move: from Gresham to Beaverton, brought me a chance to recreate myself and re-envision who I wanted to be. The high school I went to in 9th grade was far more diverse than any school or neighborhood I had lived in and I found myself only wanting to be friends or connect with my peers of color.

In class I was quiet; I did the minimum but I often skipped class or school altogether to hang out with the other Black and biracial teens in my school. Many of us were not in the same class so the only time we would see each other was at lunch and I began to take longer and longer lunches. Spending time with my peers was connecting and healing in a way I could not articulate or understand at the time, but now as an adult I look back on my freshman and sophomore years and have the fondest memories with my peers.

The downside to skipping class was I finished my sophomore year with a 1.66 GPA. I had spent the last two years out of class but with people of color. My personal and cultural safety was more important than anything. This phase of emersion would carry me all the way to college. Through a series of community & societal interventions, specifically, a program called Save Our Youth led by my mentor and friend John Ashford I was able to get the help and healing I needed, and as a result, my grades improved. Through the program, I was also introduced to the art of facilitation and the power of mentoring. I was able to see a future beyond my immediate circumstances and I attended Portland State University (PSU) focusing on a dual degree in History and Black Studies.

Stage 5: Internalization

Internalization occurs when people of color realize that there are negative qualities among our own people and that all white people are not the enemy. We see racism as the enemy and as something we can fight against. We also manifest the desire to have more control over who we want to be. We realize we are more than just a person of color.

My process of internalization began my junior year in high school when my AP History teacher connected with me in an authentic way and encouraged me to speak up about my race and the racism I saw in the history we were learning. I had always been interested in history as a topic because it was when we talked about being Black, and I wanted to talk more about being Black. My sophomore history teacher suggested I attend the class and got me into the class despite the prerequisites and GPA requirements (remember I had a 1.66 GPA, but carrying me was my A in sophomore history).

Both my sophomore history teacher and junior AP history teacher were white women and expanded my view beyond seeing white people as instruments of racism. In addition to my teachers, I had my grandparents on my mother’s side who consistently showed me love and encouraged me to be myself.

It wasn’t until a community intervention class called Save our Youth that I learned about institutional and individual racism. Learning about racism at the same time I experienced white people who were not racist began to expand my view and move me from Emersion to internalization. I stepped fully into this experience through my Black Studies classes at PSU.

Learning about institutional racism and Black history from a lens of activism and strength was healing. I learned about African sovereignty, the Black panther’s free lunch programs, pan-Africanism, and the depth, breadth, and awesomeness of Black women, Black women who looked like me. This education expanded my own pride as a Black woman and saved my life.

Stage 6: Anti-Racism

In the last stage of integrative awareness which we have nicknamed “anti-racism”, people of color come to the conclusion that there is much more to us than our race. We are able to positively identify with our own racial group while also acknowledging that other aspects of our identity (gender, talents and abilities, our unique experiences) contribute to our personhood.

College was just the beginning of my healing. At college, I was given access to healthcare, mental health, and positive peer relationships that crossed all races, ages, genders, and regions. Exploring my own identities alongside others in a diverse and supportive community cemented my commitment to social justice.

My dual major of history and Black Studies also laid the groundwork for the training sessions I lead in the workplace. My professors at college provided rigorous instruction that demanded that we, as students, question everything. I take nothing for granted and think critically when I see data and outcomes. As more and more workplaces engage in conversations about inclusion, the conversations can only go as far as the person who is the least healed. Over the last three years, I have seen many conversations derailed and stalled because of leaders who have not done their own work.

Doing our own work can look many different ways. A few options include A) individual or group therapy, B) professional coaching and C) self-reflection. I hope this blog provides an opportunity to reflect on your own racial identity and the stages and phases you have experienced over the years. We have provided reflection questions along the way and encourage you to set aside time to reflect and share in partnership with others on this journey. If you do take the time to write your racial autobiography through the identity development lens we would love to hear. Send us an email at support@constructthepresent.com or DM us on LinkedIn or Instagram. This is work we all must do and it’s so much more enjoyable when we do it together.

Author

Additional Resources

We hope that you found this content meaningful and helpful in your company’s path toward becoming an antiracist organization.

What’s next?

Continue to dig in to our Culture Change Roadmap for more best practices, core elements, and guided learning.